my favorite film these days is likely paul sharits’ 1966 film ray gun virus,1 in large part for its ability to transform the space around it. there are multiple videos on youtube demonstrating this, by playing the film in a room and training the camera on something other than the screen:

this may seem ridiculous, but the film itself is so minimal and abstract that it essentially doesn’t give you a choice: if you look away, the walls are showing just about the same thing as the screen, if you close your eyes, the colors are so vivid that you see them on your eyelids, and if you plug your ears, well, the hum of the sprocket holes crossing the optical sound reader is loud enough that escape can’t possibly be that easy. the tone being so constant means that the auditory experience of the film changes with the shape of the room, too, or in my case, how congested i am on any given day – when me and my friends threw on the film in their basement apartment, i stood up and started walking around the room, listening to the harmonics shift as i moved, appreciating how the color of their kitchen changed. one of my friends said afterwards that he watched much of the film in his partner’s eyes, because, with a film like this one, you truly can see it all in a reflection.

when i visited new york city in 2022, i made a point of booking an afternoon at the film-makers’ cooperative screening room to see some sharits prints – ray gun virus, apparent motion, episodic generation & brancusi’s sculpture ensemble at tirgu jiu. mm serra was running the place at the time, and i had her project ray gun virus for me twice; once i watched it on the screen, and the second time, recalling sharits’ claim that the film was intended as an “audiovisual pistol” targeted at the retina, i situated myself between projector and screen and stared directly into the beam to experience a headshot. i doubt he intended viewers to take that literally, but i found it fairly rewarding (if obviously eye-straining) to see these colors in a new way. his film on brancusi’s sculpture garden is a fairly low-key super 8 diary film documenting his trip to see these monumental works, but one moment has stood out in my memory – sharits gets up close and personal with these sculptures, and at one point, takes the microphone of his super 8 camera and starts scraping it against the surface of the sculpture.2 to me, this represented a totally novel way of engaging with a work of art – when i look at sculpture (not something i’m good at, frankly – it’s a medium i don’t always know how to engage with3) i certainly wouldn’t have thought to ask what it sounds like when abraded with a microphone! to me, this is what productive engagement with art looks like – asking it brand new questions and trying to discover the answers, even if those questions might not make immediate sense.

people have asked ridiculous questions of art4 since there’s been art, no doubt. hell, people (not even only me!) have done some pretty wacky things to ray gun virus – take this project by defunct (so defunct the webpages are gone, so the link is a wayback machine mirror) art duo carmichael payamps (kevin roark and bernhard fasenfest) which sorts every frame of a selection of films in color order according to various algorithms and at various speeds:

what can completely destroying the rigorous internal structure of ray gun virus teach us about it? well, in this case, i think the main thing this experiment demonstrates is just what colors dominate the composition (mostly red with a bit of green – yes, it’s a christmas movie!), but regardless of what we might actually learn, i think it’s often worth entertaining this sort of destructive engagement with a piece of art. a few years ago, i found pablo useros‘ “single-channel” cut of james benning’s films one way boogie woogie and 27 years later that, rather than placing the films (each an hour long, with each shot lasting an identical length across each film and each shot sharing a precise location and composition with the corresponding shot in the other film) one after another as they’re typically shown and exclusively distributed, puts them side by side, with the first shot of one way boogie woogie lining up precisely with the first shot of 27 years later, the second lining up with the second, all the way down the line.

naturally, i found some software that would let me view this split-screen video in anaglyph 3d, with 27 years between each eye sharing the same space in my perception, locking into a single composition. i thought a lot of one of the other films i watched during my visit to the film-maker’s cooperative, stan brakhage’s classic mothlight. i’ve seen, like, 75 brakhage films on 16mm, and while that’s obviously the ideal way to see them, mothlight is the only one i feel truly and completely fails to translate to digital video – the film itself is so uncommonly physical, even by stan’s-dards; the material pressed into the film strip is trapped in the amber of the print, which has accumulated dust and scratches of its own in the 60 years since the film was made, all of which gets reanimated by the projector. with the benning, all this was happening not with a 16mm print of a classic film projected on a wall, but happening between my two eyes, in my head, watching a janky fan-edit5 incorrectly on my laptop at 1am. maybe we’re approaching dark side of the rainbow6 territory here (or, if you’re my friend krista, throwing scatman’s world on over brakhage’s anticipation of the night), but “synchronicity” tricks like that always strike me as arbitrary,7 whereas as ludicrous as “watching two movies on top of each other in 3d” clearly is, i really do feel that it was an earnest act of engagement with the work, taking it at its own terms and doing stupid shit to it in order to discover things i couldn’t possibly have found otherwise.

earlier this month i attended a screening of margaret honda‘s film color correction, an even more radical act of transformation to a piece of source material – a random and unknown color timing tape from a film lab, printed directly to 35mm with no image to be adjusted. this is a work of art almost entirely composed of questions being asked – what movie is this the raw material from? is this shot-reverse? who’s snoring in the audience? i found it to be a pretty incredible experience, although certainly just about the outer limits of structuralism – the intellectual rewards had basically nothing to do with the soft color fields on screen, and the (expectedly) small audience was left with plenty of time to turn these questions over in their mind. in fact, it was just about their only other option besides falling asleep or leaving outright! honda is a sculptor turned filmmaker, and in interviews (and the q&a she gave after the film), she discussed color correction in those terms: the work is the physical object created from the process of printing a color timing tape, and it would have been the same work no matter what it ultimately looked like on screen – at one point she was considering creating multiples of the work, each from a different tape (resulting in completely different colors, lengths, and audience experiences). it begs the question – are we even really watching a movie, or are we at a gallery that happens to be a movie theater looking at a sculpture that happens to be a projected 35mm print created from the raw materials of film production? where does the work end and what we bring to it, what we ask it, what it asks us, begin? when we watch color correction, if we’re watching closely, we can start to maybe recognize the rhythms of what we know as traditional cinematic grammar, but only vaguely, and even then, these readings are only really happening in the viewer’s subjective experience.

on the subject of grammar, i read gertrude stein’s tender buttons last year and, while i ultimately quite liked it, i definitely struggled a bit seeing such fractured language rendered as paragraphs of prose, so i did something fairly irresponsible: i “translated” it into something that closer resembled what i was used to from poetry by taking the full text, finding + replacing all commas with line breaks and turning periods into stanza breaks. it must be said: this is dumb. this is not any sort of way to read tender buttons. it turns a method of a cloak, for example, from…

a single climb to a line, a straight exchange to a cane, a desperate adventure and courage and a clock, all this which is a system, which has feeling, which has resignation and success, all makes an attractive black silver.

into…

a single climb to a line

a straight exchange to a cane

a desperate adventure and courage and a clock

all this which is a system

which has feeling

which has resignation and success

all makes an attractive black silver

obviously, these are pretty different things, and i did not read much of tender buttons in my mutilated form (that would hardly be reading tender buttons at all), but even giving this cut-and-paste job8 a once-over felt fairly illuminating as to what sorts of repetitions i should be reading for, how to get a handle on the rhythm even when it’s presented so radically.

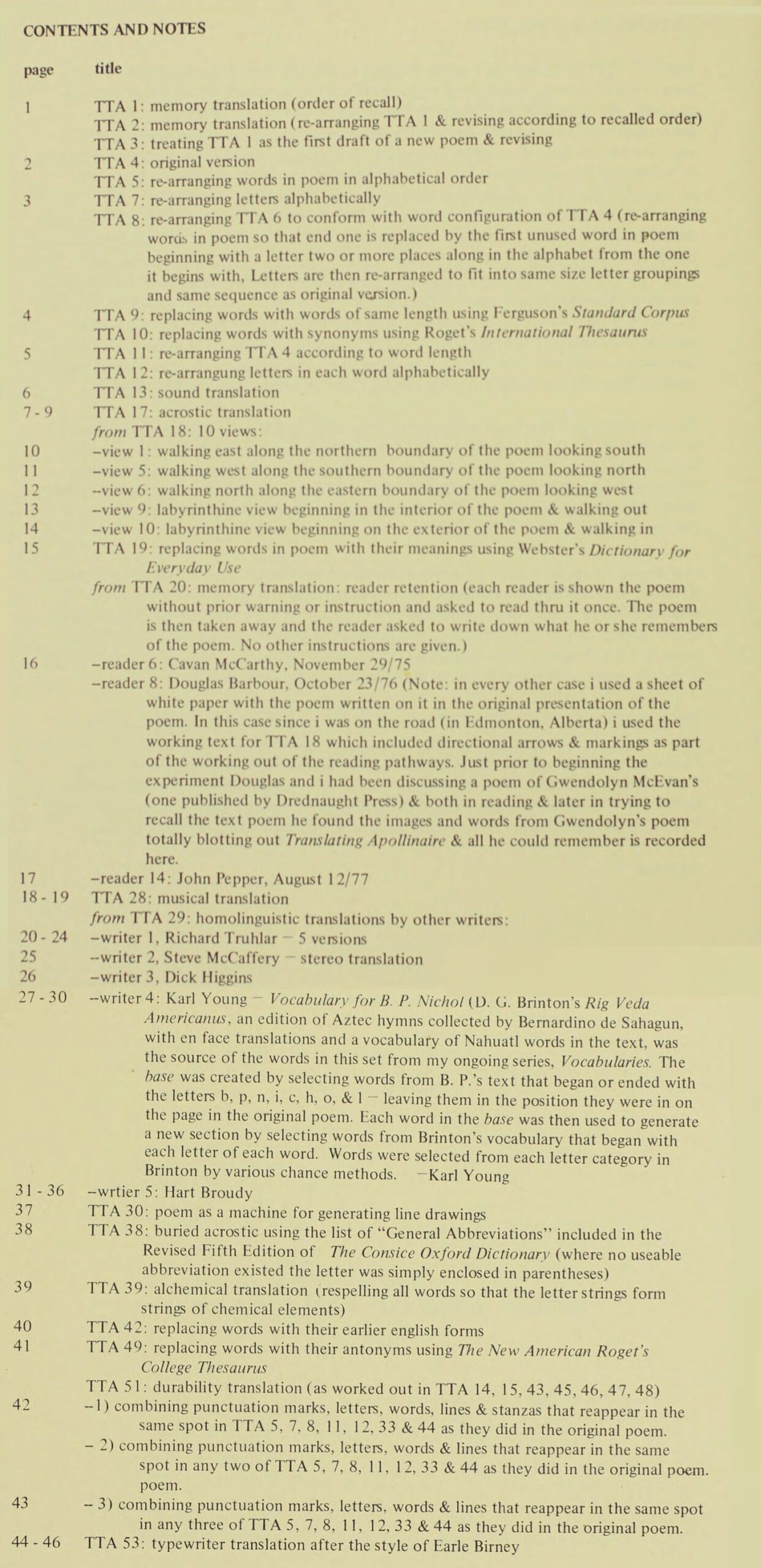

this idea of “translating” poetry by completely tearing it apart is one i got from canadian poet bpnichol’s remarkable chapbook translating translating apollinaire: a preliminary report, which the poet’s estate has graciously posted online. check out the table of contents for a brief overview of just how broad his definition of translation is:

how exactly does one read a “poem as a machine for generating line drawings”? well, you trace each word9 on a coordinate grid, of course!

i love this sort of thing – it’s the same part of my brain that drove me to take notes via spreadsheet while watching hollis frampton’s film zorns lemma, and while that didn’t ultimately reveal any hidden patterns, the act of putting in the effort to ask the work if they’re there feels to me like meeting the art where it’s at and seeking to learn as much as you can from it, which will always be worthwhile.

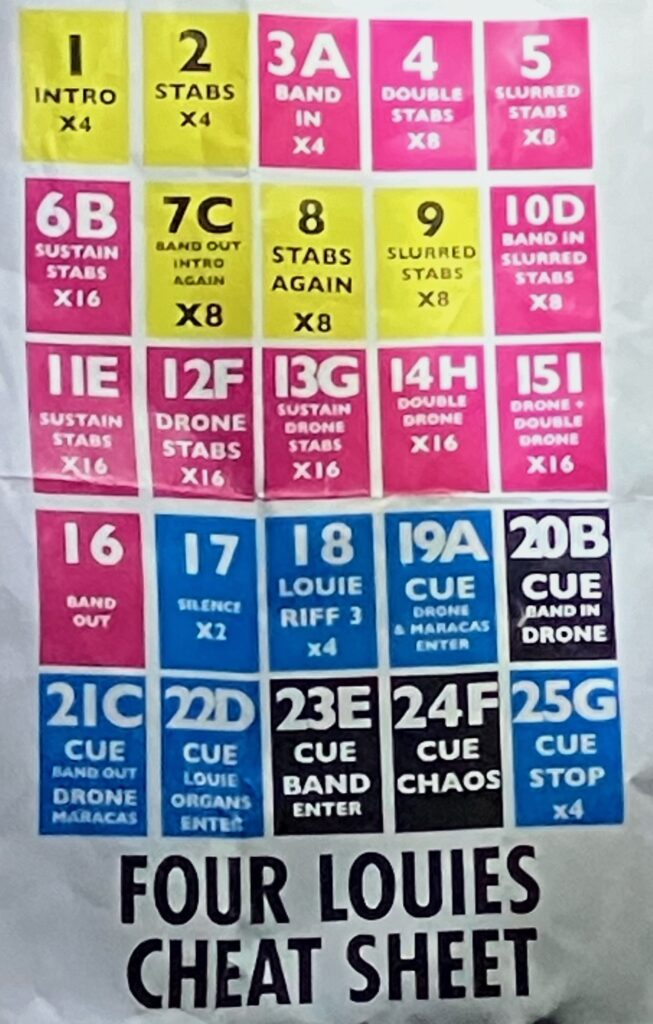

last night at zebulon here in la i saw bill orcutt joined by a 12-piece band to play a live rendition of his initially-computerized piece the four louies. i’d seen bryan day at trade school in altadena the night before (a great set, noise table by way of hans reichel’s daxophone, full of cartoonish piezo noises, clattering percussion and rolling feedback) and learned he was in town to play as one of seven organists in bill’s band – the four louies is, of course, a mashup between louie louie and steve reich’s four organs, an idea so good that once someone makes the connection it seems like it ought to have been obvious from the start. how could i miss it? the four louies was initially part of bill’s fake estates series, which are to the best of my understanding all made with his bespoke live-coding software cracked (excited to go down that rabbit hole), often from samples from existing music – an earlier installment in the series was a mechanical joey, another great idea, although i admit, i’m biased, as i also was fooling around with the idea of recontextualizing punk-rock count-offs as einstein on the beach knee plays! the show last night aimed to bring the four louies from theoretical computer cut-up to live rock and roll performance – seven organists, two guitarists, two drummers, a bassist, and, because this is ostensibly four organs, a maraca player with the unenviable job of anchoring the pulse for the whole piece.

in lieu of an opening act, bill hit play on another fake estates album, the anxiety of symmetry – like a mechanical joey, it was a glass-ish thing with patterns being counted out loud in shifting relations. bill explained that he often performs it live in software, but was too nervous about the four louies (fair, it was the first performance) to do anything more than drop the needle on the record and let us listen at earplug-necessitating volume in a rock club. interesting album – had some lovely passages, certainly, and the sampled looping voices give the thing a slightly different feel to a glass piece where human voices are singing; each “one,” “two,” “three,” etc, being an identical sample means that the plosives and fricatives of each number are exactly the same every time, which means that out of the mist of voices you can pluck some fairly consistent and coherent rhythms that start to sound a bit like abstract techno drum programming. it was nice, but it wasn’t really a live show in any way, and i admit that i didn’t love sitting through a whole record at a concert (i can do that at home!10), so i was kind of jittery and frustrated waiting for the band to show up.

four organs is one of reich’s first attempts at applying his doctrine of “music as a gradual process” to an instrumental ensemble – the maraca keeps the beat while the organists slowly trace out the shape of a single chord, eventually devolving from an insistent stomp to a swirling drone over the course of 15 or so minutes. louie louie (as played by the kingsmen), on the other hand, is a rock standard that marches along on the strength of an unchanging organ riff and only holds itself together by sheer muscular force of will. the way to combine them in a live performance: follow the scripted process, but embrace the chaos.

once you hear the connection between the two works, you can’t ignore it. reich wasn’t writing garage rock and the kingsmen didn’t set out to play contemporary classical, but there on the zebulon floor (where the audiences for avant-garde sound art, hipster dance parties and rock concerts intermingle just about every evening), the four louies, far from a conceptual gag, made just about perfect sense, as if it were inevitable. neither artist could imagine their work being used this way, and yet here we were – at ear-splitting volume, as undeniable as it gets. maybe it’s a bit of a joke, maybe it’s a noisy rock show, but whatever it is, above all else, it’s serious critical engagement with musical tradition, no matter how playful and absurd it may be.

earlier this morning i visited lisson gallery’s los angeles outpost to see a few drawings they had on the wall by the late channa horwitz.11 since seeing one of her drawings at a lacma exhibit on computer art a few years ago (she didn’t use a computer in her practice and resented being lumped in with computer artists, but i gotta be honest, it’s easy to see why she was), she’s been one of my very favorite artists. one of her major series that she worked on throughout her career was what she called sonakinatography – these pieces are usually exhibited and sold as works on paper, but what the term technically refers to is her idiosyncratic and highly systematized notation system12 for time, movement and rhythm. the pieces that are labeled as “sonakinatography” are all exquisitely detailed pieces of graphic design, but the work itself is less the resulting drawing as much as the process she followed to render it on paper – key to this is that the process can be followed in other mediums. she was a graphic artist, but her “compositions,” as she called them, could be performed by dancers, lighting designers and musicians, all of whom have tried their hand at her sonakinatography composition iii.

i was interested in performing her works as a musician, so last year i got in touch with her daughter ellen davis, who heads her estate. ellen taught me how to read composition iii (it involves some pretty easy to grasp but very difficult to explain multi-leveled counting of the sort that late composer tom johnson wrote about in his excellent book self-similar melodies) and sent me home with a decently high-quality scan of the score, which i’m certainly not going to be the first to upload to the internet,13 so instead please accept the first 70 steps of my own transcription in microsoft excel (which runs to 314358 steps and shows no sign of repeating itself anytime soon – i believe the algorithm would only repeat itself after 437,951,584,980 steps!).

don’t worry about how to make sense of this right now, just know that i’ve been trying on and off for the better part of a year to figure out the best way to translate it into a performable and coherent piece of music and haven’t really made much headway. reich’s notion of process music is a key reference point for me as to what a satisfying musical rendition of the composition would entail – reich makes it clear that a big part of the success of a piece of process music (by his definition, one i tend to share when working with processes this abstract), the listener ought to be able to parse the process through the audible experience. this is pretty easy in a piece like four organs, where it’s pretty difficult to ignore what’s happening, but is a lot harder to do in a piece with no agreed-upon musical setting whatsoever!

since my recent wrestling with sample-level digital audio14 was still fresh in my mind, and horwitz gave a fairly straightforward algorithm to follow with simple numerical results, i was curious if the way to hear this process was to sonify it directly. essentially, i’d treat each step in the composition as a sample in a buffer and treat the values on that step as the sample value (summing them up). for example, if you look at the transcription above, step 1 would have a value of 1, step 2 would have a value of 2, steps 3 and 4 would have a value of 4, 5 and 6 would have a value of 7, and so on, 44100 steps a second (with the sample values scaled to between -1 and 1 rather than positive integers). what on earth would this sound like? would the process become audible when turned so directly into sound? i tried it out – be warned that the audio file that follows is a loud and high pitched sound, so turn your volume down.

is this interesting to listen to? i don’t think so. is it timbrally dynamic? not particularly. are you able to hear the process unfolding? i sure ain’t! was it a question worth asking and an approach worth exploring? of course it was!

- if anyone is able/willing to sell me a 16mm print… let me know lol. i mean it! ↩︎

- artist richard lerman tends to foreground the mechanical production of sounds in contexts where we usually aren’t thinking in terms of sonics in his work, but i’m not sure even he attempted to wrestle with a sculpture quite like this! ↩︎

- i like richard serra’s big cor-ten things, ultimately for similar reasons i like ray gun virus – they radically redefine/create an environment with all the subtlety of a sledgehammer and zero aesthetic pretense – but much of the time sculpture eludes me. skill issue on my part! i’m workin’ on it! ↩︎

- check out the great deborah stratman responding to perhaps the most absurd question i’ve ever heard – chairs have five legs… ↩︎

- steven soderbergh is the king of this, of course – never not thinking about him spending his so-called “retirement” cutting other people’s movies without permission for fun just to see what he could learn about how they work, iconic, all artists ought to be so curious ↩︎

- i mean, the movie already has a soundtrack! live scoring films is one thing – i’ve even done it a few times, once as part of intergenerational noise rockers gang wizard (although one of the films we scored was ballet mécanique, probably as famous for its soundtrack as it is for the filmmaking) and another time at martha colburn & pat o’neill‘s barn as impromptu accompaniment to pat’s film screen – but at least those are live reactions feeding off the extant work of art rather than just putting two fixed, finished things next to each other! how can they possibly interact? ↩︎

- john fell ryan and akiva saunders’ the shining forwards and backwards is obviously not arbitrary, but it feels strange to me to find it revelatory that a movie has a structure, doubly strange to lump that fact in with woo about synchronicity – it’s not that deep, gah! ↩︎

- i read a collection of poet jackson mac low’s work a few months ago and did not particularly like a lot of it, but the stuff i really dug was his algorithmic reworkings of stein, which used custom software (based on processes he initially performed by hand) to navigate gertrude stein’s writing and rearrange her words into brand new orders. i found the examples given of his works with stein as source text pretty striking in ways that actually do meaningfully differ from (and perhaps even occasionally build on) the original, and am excited to check out the complete stein poems, which are being published in their entirety later this year. ↩︎

- artist michael winkler has devoted practically his whole career to doing things like this with language, and while he also often approaches mystical territory that i think is ultimately pretty silly, i quite like his work and writing on the subject – even when it’s not quite as rigorous as it claims to be, it’s still an admirably comprehensive project; “what does language look like within this framework i came up with” doesn’t necessarily reveal universal truths, but it does create a pretty interesting and by nature hermetic artistic practice! ↩︎

- felt the same way when i went to a xenakis “concert” that ended up being simply quadrophenic audio playback. sure, it’s a nicer sound system than i could listen on, but isn’t the whole point of experimental process-driven music like this to see people bring it into acoustic reality? always a bit disappointing. ↩︎

- i’m always a bit uncomfortable at galleries because i’m an enthusiast rather than a collector, but they seemed happy to show someone who wasn’t planning on buying around, thankfully – “refreshing” for someone to be there to actually see the art! the main room had a carolee schneemann show, largely centered on her installation piece video rocks, which was quite delightful. i signed the gallery’s visitor/guestbook and the name above mine was paris hilton – i’m choosing to believe it’s the real her and that, in addition to allegedly being a vintage radio collector, she’s also a schneefann! or maybe a fann-a’ horwitz… ↩︎

- note to self and all interested people, who likely include those of you reading the footnote on unconventional notation: the getty research institute recently released their new online publication the scores project: experimental notation in music, art, poetry and dance. i haven’t dug in yet and am very excited to. despite the getty research institute having a few of channa horwitz’s works in their library and her art falling, as far as i can tell, directly under the purview of this project, it seems to focus more on east coast, fluxus-aligned artists. and yet basically no paul sharits either! tragic… he made scores as a critical part of his practice too, you know! ↩︎

- because she was a woman making conceptual, sui-generis art in the 60’s and 70’s, horwitz is often a footnote in histories of the movement, and there is a frankly depressing lack of writing on or information about her on the internet or in print. i am lucky to live in los angeles, where she lived and worked, where her archive is kept, and where multiple institutions collect her work, but even so, high quality reproductions of much of her work are not easy to come by. ↩︎

- amy goodchild’s ai versions of sol lewitt’s wall drawings, which i mention briefly in that post, are also great examples of approaching art in an extraordinarily silly and obtuse way that generates pretty useless results in an attempt to learn not only more about the work but more about our tools and frameworks. ↩︎